Judge Benjamin Hayes knew the eyes of Los Angeles were on him. In January 1856, the hard-living judge presided over a hearing that would rock Los Angeles, a dusty, dangerous pueblo of approximately 4,000 souls. Out of the hearing would emerge Biddy Mason, a formerly enslaved woman who would become one of the most important — and one of the wealthiest — landowners, midwives and philanthropists in early-American Los Angeles.

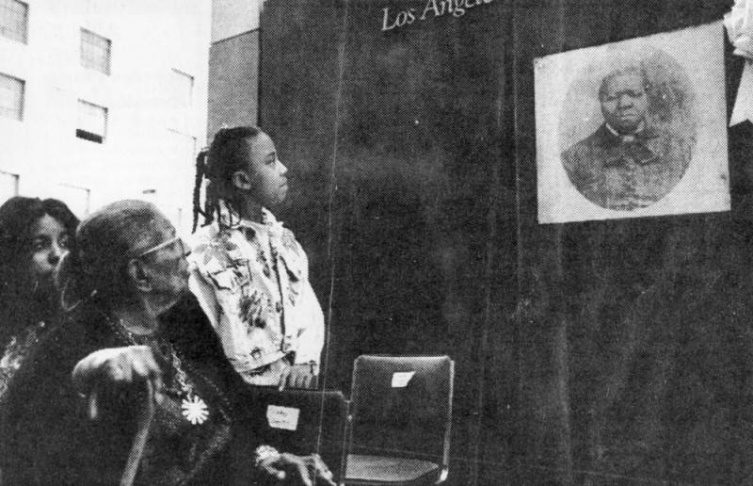

Mason was so beloved that people in need would line up in front of her house on First Street, eager for “Aunt Biddy’s” assistance, which she always gave until she grew too old and infirm. “She showed people what could happen when they were free and could set their own destiny,” says Jackie Broxton, executive director of the Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation.

Nearly 170 years later, Mason’s spectacular journey continues to inspire people in Southern California and beyond. The foundation that bears her name uses her story to uplift and serve L.A.’s foster youth. This Thanksgiving, the organization gave grab-and-go holiday dinners to more than 400 people impacted by the foster care system.

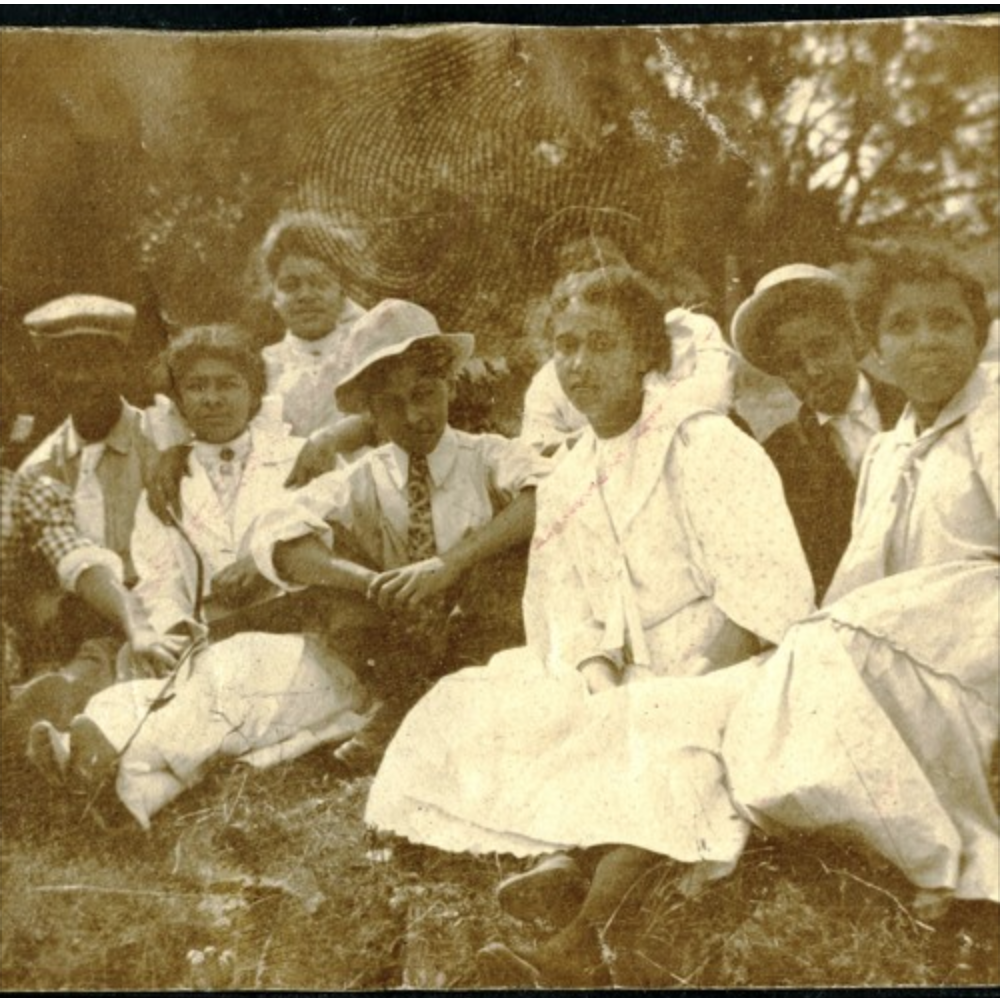

Mason’s legacy also helped save a group of W.P.A. murals, painted by Bernard Zakheim, on the U.C. San Francisco campus. After Laura Voisin George came across a depiction of Mason in the frescos, which were scheduled to be destroyed, she alerted Dr. Kevin Waite, an Assistant Professor of History at Durham University in the U.K., and a fight began to save them. The university eventually bowed under pressure from several groups, as well as Mason descendants Cheryl and Robyn Cox, and has hired a conservator to preserve the frescos (although it has no plans to exhibit them publicly).

Despite Mason’s enduring regional fame, her story is often retold using the same handful of anecdotes with few concrete facts to back them up. Dr. Waite and Dr. Sarah Barringer Gordon, a Professor of Law and History at the University of Pennsylvania, want to change this. As co-directors of a three-year collaborative grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to research Mason’s life, they have been digging deeper into her story.

In the process, they have not only illuminated details of Mason’s story, they have shined light on the history of Los Angeles and the United States in the early and mid-1800s. It is a tale of new religions, old prejudices, ingenuity and resilience.

The Journey Begins

Biddy Mason was born into slavery, probably in Hancock County, Georgia, in 1818. Although many details of her early years are a mystery, Waite and Gordon have tracked her major movements. She was forcibly transported to Mississippi in the early 1830s. In the early 1840s, she was purchased by Robert Smith, a moderately successful Mississippi landholder who almost certainly planted crops and traded slaves.

“He definitely didn’t rise to the status of ‘planter,’ which is defined as anybody with 20 or more slaves, but I think it is safe to call him a modest buyer and seller of human property,” Waite says.

Smith likely cultivated cotton, the South’s most important crop, and Mason probably had experience doing both domestic work and farm labor.

“She was known as a particularly strong woman physically, and she would have been valuable in the field,” Gordon says. Mason also gave birth to three daughters — Ellen, Ann and Harriet — whose paternity is unknown. Harriet may have been the child of Smith or another member of his family.

Mason was probably familiar with the teachings of the Mormon Church, since Robert Smith was a convert to the new faith, which had been founded by Joseph Smith (no relation) in 1830.

“In the early 1840s, there was a very successful Mission movement to Mississippi, and at least 200 people were converted. Then, in the late 1840s, the great Mormon Exodus to Utah included a large contingent known as the ‘Mississippi Saints,’ of which Robert Smith was one,” Gordon says.

Although Mormons were better known as opponents of slavery before the assassination of the Joseph Smith in 1844, church teachings and policy evolved later in that decade and during the 1850s to a more clear pro-slavery stance.

“According to the leaders of the church, slavery was sort of a condition imposed upon the descendants of Ham [i.e. those of African heritage]… Their argument was you cannot release these people from bondage until God himself releases them. So, bondage is a divinely ordained institution, and the patriarchs of the Old Testament practiced it, so present-day Americans [could] practice it as well,” Waite says.

Mormons were encouraged to treat their enslaved people kindly, since they saw them as lesser humans who needed the white man’s protection.

In 1848, the Smith family began their trek West. Mason, her daughters, a woman named Hannah and her children were forced to join them on the brutal, roughly 1,600-mile trek from Mississippi to Utah. Mason probably walked much of the way behind the wagon, herding livestock.

“The trail must have been disturbing, frightening and strange, but if an enslaved person was in a position to escape, that was an opportune moment, especially when there were anti-slavery sympathizers nearby in several states, including Iowa and parts of Kansas,” Gordon says. For this reason, enslaved women’s value increased on the trail since, like Biddy and Hannah, they often had young children and were less likely to try to flee.

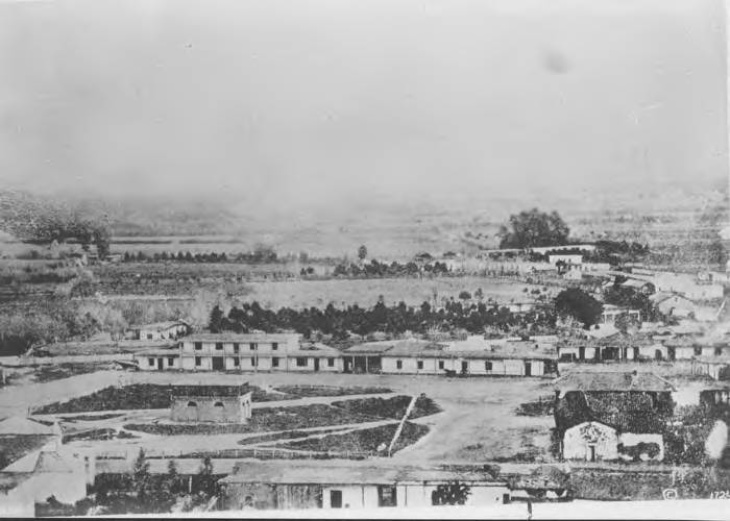

The Smiths spent time in the pro-slavery Mormon settlement of Cottonwood Canyon, Utah before coming to California in 1851 to help settle the Mormon colony of San Bernardino. Moving to Southern California, “Biddy was stepping into a world controlled by a clique of mostly white Southern men and their Latino allies,” Waite says.

Although California joined the United States as a free state in 1850, the laws around slavery were complicated.

“When [Biddy] arrived in California, she arrived in a technically free state. But it was a land made up of unfree laborers of various kinds,” Gordon says. Indigenous people could be forced to work as “contract laborers” (essentially indentured servants, but with no ability to leave) or declared wards of white and Californio elites.

As Waite explains, during the 1850s, Los Angeles contained what observers called a “slave mart.” Every weekend, local authorities would arrest intoxicated Indians on dubious vagrancy charges. They would then throw the Native Americans in a pen and auction off their labor for the coming week. “If they were paid at the end of that week, they were usually paid in alcohol so they could get drunk, be arrested and begin the process again,” he says.

This “slave mart” was the second most important source of municipal revenue in L.A., after the sale of licenses for saloons and gambling venues.

For a time, Smith prospered in San Bernardino, where Mason probably worked alongside Native Americans who had been forced into indentured servitude.

“Smith was one of the counselors to the bishop [a local leader in the Mormon Church] and as an owner of… 13 enslaved women and children, and an owner of a very large property, he would have been among the wealthiest settlers in San Bernardino,” Waite says.

Smith, a difficult and argumentative character, kept butting heads with Mormon leaders in San Bernardino. According to Waite and Gordon, the Mormon colony began to fall apart after its leaders made a terrible real estate deal, paying top dollar for what they thought was 80,000 acres of land when they had actually purchased only 35,000 acres. Unable to pay off their loans, the colony sued the people who had sold them the land.

They lost, likely because church leaders did not read the fine print. But the court allowed them to choose up to 35,000 acres anywhere in the larger area. Eventually, they chose Smith’s ranch, among others, to be turend over to the church without any compensation. “Smith and many others were outraged and there was widespread dissent, and Smith made plans to leave the colony – but quietly and with no open confrontation,” Gordon says.

In 1855, Smith broke with the Mormon leaders of San Bernardino and was eventually excommunicated from the Church. He sold off his cattle and prepared to move to Texas. Before he left, Smith took his family and slaves to a camp in the Santa Monica Hills, probably to obtain provisions for the journey eastward. Waite also notes Los Angeles was considered a hospitable place for slaveholders, since many early Angelenos were originally from the American South.

“Maybe by camping closer to fellow Southerners he felt more secure. Maybe he just happened to know people in the area. We have yet to come across a hard and fast answer for that one,” Waite says.

In December 1855, someone tipped off local authorities that a group of Black Americans were being held in Santa Monica Canyon and were about to be taken across state lines to the slave state of Texas.

Until recently, Smith would have been within his rights to take Mason and her compatriots out of California — but not to Texas. The California Fugitive Slave Act, enacted in 1852, allowed slave owners to temporarily hold enslaved persons in California and transport them back to their home state. But the code had been allowed to lapse in April 1855, and would not have applied to Smith, since he was moving to Texas not Mississippi.

On New Year’s Eve of 1855, two sheriffs, one from San Bernardino and one from Los Angeles, approached Judge Benjamin Hayes to issue a writ of habeas corpus. According to Gordon, writs of habeas corpus were widely used against slaveholders in free states.

“It’s a writ issued by a judge, which commands an individual to produce those who are alleged to be unlawfully imprisoned or confined,” Gordon says.

Hayes issued the writ and late that night, sheriffs raided Smith’s camp in the Santa Monica mountains, taking Biddy, Hannah and their children into protective custody. They brought them to the city jail at the corner of Spring and Franklin Streets in downtown L.A.

Law & Order

It has long been a mystery who exactly tipped off the authorities. In her masterful essay, Biddy Mason’s Los Angeles, 1856-1891, historian Dolores Hayden claims it was Elizabeth Rowan, a formerly enslaved woman who had also settled in San Bernardino, along with prosperous downtown Los Angeles livery owner Robert Owens.

“The Owens family ended up working for the U.S. government in the Civil War, supplying horses, and they were well-known and respected as free Black persons,” Gordon says. She and Waite think Mason may have met the Owens family when Smith went to Robert, a horse dealer and outfitter, to prepare for the journey to Texas.

Broxton, the executive director of the Biddy Mason Charitable Foundation, believes the small community of free Blacks in Southern California would have been moved by the women’s plight.

“Smith stood out like a sore thumb because here he comes bouncing into town… after California has been admitted to the U.S. as a free state, with 13 slaves. That’s not the smartest thing he could have done. And there were already Blacks here who were free, so with their common experience, they are going to want to do something to help her,” Broxton says.

The secrecy surrounding the origin of the complaint lends credence to it being a person of color. Many habeas corpus writs are issued at the request of local sheriffs, however, and it is also possible that happened in this case. Given the controversy surrounding the litigation, anonymity for the complainant would have been a welcome protection.

“This was a very carefully kept complainant. There could be several different reasons for that. One might be that no person of color, no Native or Negro [according to] an 1850 statute, was allowed to testify in any case involving a white person. So if the complainant was a person of color that would have been a violation of the statute,” Gordon says.

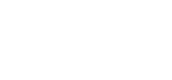

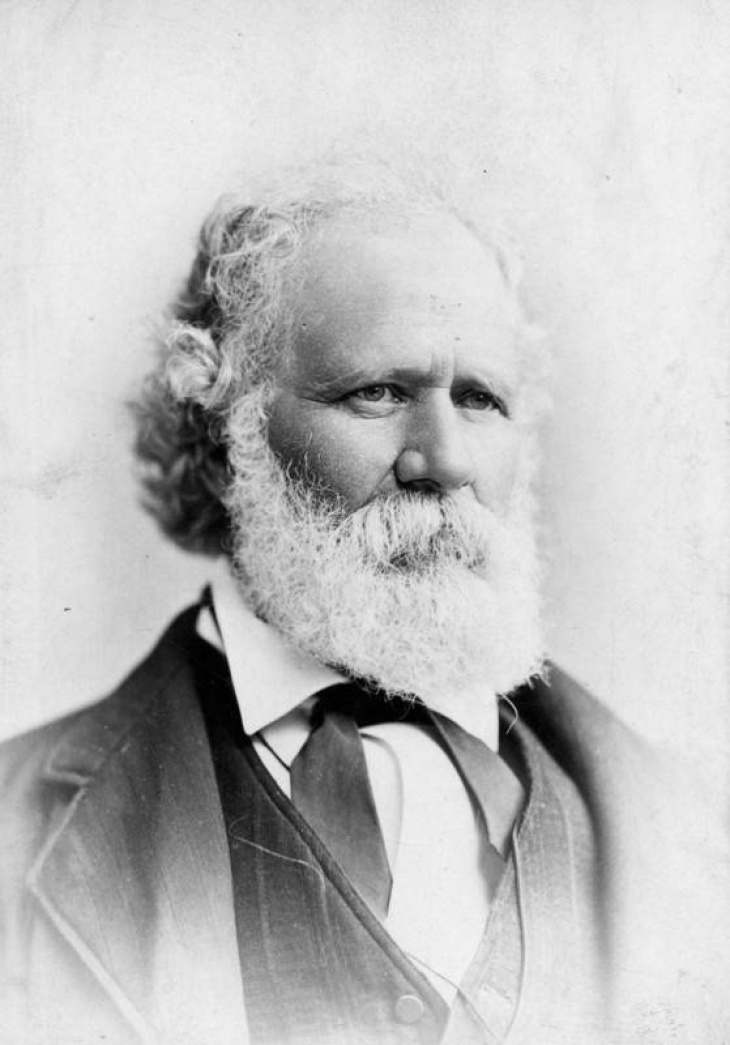

On paper, Judge Benjamin Hayes did not seem like someone who would be on Mason’s side.

Born in the slave state of Maryland, Hayes had briefly owned slaves through his wife before moving to Los Angeles. In his work as a journalist, he had written-pro Mormon articles in the past, painting them as industrious and admirable people. He had even gone to San Bernardino on his court circuit as a judge. He had also met with Mormon leaders about a construction project and noted casually in his diary that there were Black “servants” present at the settlement.

As Los Angeles residents celebrated the new year, both sides geared up for the trial. According to Waite and Gordon, Biddy Mason was allowed to stay with the Owens family, although the children were kept in protective custody at the local jail.

The hearing on the writ began on Saturday, January 19, 1856, in Judge Hayes’ downtown L.A. courtroom.

Hannah, who had given birth to a baby boy only two weeks earlier, testified. Surprisingly, she said that she wanted to go to Texas.

“She gave this unbelievably damaging testimony even though she clearly hated doing it. There were long silences,” Gordon says. “Then she left to return to San Bernardino. [Judge] Hayes sent the San Bernardino sheriff up to talk with her and she said, ‘I promised I would say in court that I wanted to go but I don’t want to go. If you bring me back to court, I’ll say I want to go but I don’t want to go.’ So the sheriff came back and submitted an affidavit saying she doesn’t really want to go.”

Hannah was probably terrified of what Smith would do to her if she refused to go with him to Texas. His behavior before and during the course of the hearing made it clear she had good reason to be afraid.

“Robert Smith behaved really, really badly during the course of the hearings… The lawyer who had been retained for the petitioners was threatened and abruptly withdrew from the case in return for a bribe of $200. Smith’s son and trail hands went to the jail with alcohol and tried to intimidate the jailer and lure [Biddy Mason’s] daughters away from the jail. They also threatened the Owens family and a neighborhood grocer and a doctor. They said ‘If this case isn’t resolved on Southern principles, you’ll all pay the price, all people of color.’ They really behaved like thugs, and you can imagine how Smith’s credibility was eroded,” Gordon says.

Judge Hayes was furious with the Smiths and clearly rattled by what he had heard.

“What I think surprised him and disturbed him was that Robert Smith was trying to take these people out of California, and that he lied about their own wishes,” Gordon says.

According to Hayden, since Mason, as a Black American, could not testify against Smith, a white man, under state law, Judge Hayes took her into his chambers along with two trustworthy local gentlemen who acted as observers. (He also questioned her elder daughters.)

“He asked her only whether she was going voluntarily, and what she said was, ‘I always do what I have been told, but I have always been afraid of this trip to Texas,'” Gordon says. According to Hayden, Mason was clearly unwilling to go to Texas, and she may have had Hannah’s tacit approval to say so.

That day, Judge Hayes (according to a document printed in historian Delilah Beasley’s book, Negro Trail-Blazers of California) issued the following preliminary holding:

“And it further appearing by satisfactory proof to the Judge here, that all the said persons of color are entitled to their freedom and are free and cannot be held in slavery or involuntary servitude, it is therefore argued that they are entitled to their freedom and are free forever.”

This opinion was not a final ruling although it is often reported as such.

“As you can see, it’s ‘argued’ rather than ‘held’ but it does seem like Hayes, on this initial hearing, had made up his mind. Judge Hayes also ordered Smith to bear all costs associated with the case and caring for those placed in guardianship of the sheriffs as they prepared for trial” Gordon says.

The trial was scheduled to continue on Monday, January 21, but Smith was a no-show. Unwilling to pay court costs and knowing his name was now mud in L.A., he ran off to Texas where he would establish himself as a cattle rancher. He died in 1891 and was buried in Mormon temple robes.

“Before the case was resolved, he scarpered. There was nobody being held against their will, so the case ended because the defendant disappeared. It ended not with a bang but a whimper,” Gordon says.

With Smith gone, Mason, Hannah and their children were released from protective custody. Hayes proclaimed that “Biddy and Hannah, the two adults, could consent to go voluntarily, if they wanted to go to Texas, but they could not bind their children into slavery,” Gordon says.

Hayes’ actions would have a disastrous effect on his reputation.

He was accused in pro-Confederate Los Angeles of being an abolitionist. He occasionally arrived to work so drunk that court had to be shut down until he sobered up. In 1863, he lost his judgeship. But he may have felt his ruling in the Smith case was a case of kismet.

According to Gordon, in 1886, Hayes wrote a letter to a friend stating that although he had paid a terrible price for doing the right thing, he suggested it had been worth it when his son, who had been thrown out of a wagon and was about to be crushed by its wheels, was saved by one of the women he had freed. Hayes never mentioned which woman it was.

Building A Legacy

Mason and her daughters were now citizens in rough-and-tumble Los Angeles, where only around 80 of its 4,000 residents were Black. She seems to have stayed in Judge Hayes’ orbit, becoming a nurse and midwife to his brother-in law, Dr. John Strother Griffin, another former slave owner. She also remained closely entwined with the prosperous Owens family, who she lived with for 10 years. Her oldest daughter, Ellen, married Owens’ son, Charles.

According to Waite, Hannah remained in San Bernardino with her husband, Toby Embers. Sadly, he was murdered by a drunk white man two years after Hannah won her freedom. Her daughter, Ann, moved to L.A., married and had seven children. She and her family were neighbors of Ellen and Charles Owens.

Together, Mason and Dr. Griffin would deliver hundreds of babies. The Griffins were prominent L.A. landowners and may have encouraged or inspired Biddy to begin buying property. She may have also learned about real estate opportunities from Robert Owens, a successful landowner himself, according to Gordon and Waite.

According to Hayden, Mason bought her first lot in downtown L.A. in 1866 and continued her real estate ventures for the next three decades. Increasingly wealthy, she eventually had more than 20 tenants, three substantial plots near what is now Grand Central Market as well as land on San Pedro Street in Little Tokyo.

“Once she got her freedom, she didn’t accept ‘no’ for an answer. Whatever she set out to do, she was very methodical about. She had to be a tremendous person with strategy because nothing appears to be accidental. It all appears to be very well thought-out,” Broxton says.

Broxton is currently trying to definitively locate all of Mason’s land holdings and hopes to put a plaque on each spot. She says it makes perfect sense that Mason would become a real estate dynamo.

“Slaves knew the value of property more than anybody else because they were property. They were bought and sold on a whim, so they understood the value of money and property,” Broxton says.

Mason also continued her work as a midwife and nurse, becoming a beloved figure in the community. Although she could not read or write, Broxton says she learned to speak Spanish fluently, probably to communicate with her patients.

“She was clearly one of the most charming and effective people anyone ever met,” Gordon says. “She got along with very eminent people who were happy to see her, as well as newcomers who came to her for help and advice…She was a well-known figure in L.A. and deeply appreciated.”

Mason was also a noted philanthropist in a town full of hard-luck desperados.

“Los Angeles was a hellhole of a place. There were a lot of people who were in trouble for a lot of different reasons. She would provide food for them, she’d provide shelter for them, she’d make contact with the local grocer after floods and instruct them to put everything on her bill, she would go to prisons and treat people with smallpox,” Broxton says.

By the time Biddy Mason died in 1891, Los Angeles had become a bustling city with 50,000 residents.

“This old Frontier Town became an emerging metropolis… She saw it transformed before her eyes and she took part in that transformation,” Waite says.

It was a remarkable journey for a woman born into slavery and forcibly moved across the country to a region she knew nothing about. Biddy Mason asserted her freedom, protected her children, built a legacy of generational wealth and helped hundreds of Angelenos in the process. In Gordon’s words, “She made her place.” More than that, she had taken Los Angeles and made this place her own.

Read the original article here.