Four hundred years since the first captive Africans were dragged onto the shores of North America, interest in the history of slavery is at a new high. Media and scholarly debate has proliferated in the wake of the 1619 Project, among other major works. Yet the centuries-long tradition of Native American enslavement — what one historian calls “the other slavery” — remains a blind spot.

Slavery in North America predated the arrival of European colonizers. Indigenous peoples across the continent raided rival polities and seized captives, who they treated as sources of labor or even as adopted family members. But after the European invasions of North America in the 16th and 17th centuries, trade in indigenous slaves became commodified and endemic. By the end of the 19th century, historian Andrés Reséndez estimates, somewhere between 2.5 to 5 million Native Americans had fallen victim to enslavement.

Utah played an overlooked role in this history. As the first Latter-day Saints carved settlements from Utah’s arid landscape in the mid-19th century, they supplemented their own hard work with hundreds of coerced Indian laborers, mostly children. These practices persisted long after the 13th Amendment (1865) outlawed slavery in the United States.

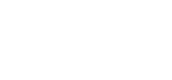

Initially, it seemed that LDS leaders would resist the slave economy of the Southwest. Church President Brigham Young condemned the practice of raiding indigenous groups to seize captives, a popular source of labor in the region for hundreds of years. Instead, he and the Mormon-controlled legislature of Utah crafted what they believed was a more benevolent policy.

In 1852, Utah passed “An Act for the Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners.” The statute allowed white residents to purchase Native children for “adoption” into their households for up to 20 years. These children worked for Mormons as captive domestic laborers, performing many of the tasks necessary to maintain life on the frontier in order to repay the price of their own purchase.

Altruism underlay Utah’s adoption policy. According to the Book of Mormon, American Indians belonged to a fallen tribe of Israel called the Lamanites. LDS leaders argued that, through education and assimilation, the Saints could remove the Lamanites’ mark — i.e. their dark skin — and transform them into a “white and delightsome people.” Adoption was to facilitate this salvation – what some Saints called “purchasing slaves into freedom.”

Framed as charity, the law instead deepened the kind of captive raiding Young had hoped to avoid. In one infamous incident, the “adoption” of Indian children followed the massacre of their parents. At Circleville, Utah, in 1866, LDS settlers herded some 30 Paiutes into a church meetinghouse. The next day, they executed all the Paiute adults, while deliberately sparing the children. One boy was later sold for a horse and a bushel of wheat.

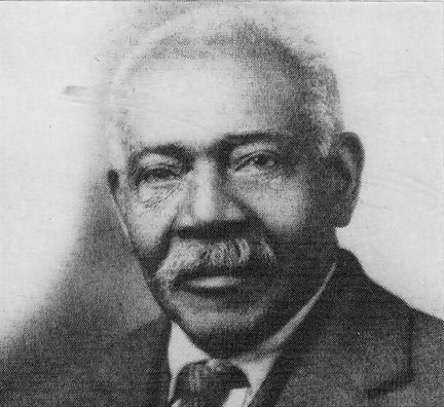

According to one study, more than 400 Native children were forcibly taken into LDS households between 1847 and 1900.

Some 60 percent of Indian adoptees died by their early 20s. Those who survived generally found themselves without a community, full members of neither their original tribes nor the white communities in which they were raised.

Given the tragic human toll of this commerce, why has a discussion of Native American captivity largely escaped the current debate over American slavery and its legacies?

It’s partly a matter of visibility. By 1860, roughly 4 million African Americans lived in slavery. Their coerced labor fueled the American economy in the 19th century. Indigenous slaves are harder to count, and the product of their labor is harder to quantify. They often worked in domestic settings, rather than on the enormous plantations of the Southeast.

Native American enslavement is also harder to classify. A vast range of coercive practices — forced adoption, “guardianship,” debt peonage, convict-leasing, vagrancy legislation, and more — existed across the North American West.

There are meaningful distinctions between African American slavery and the “other slavery” that millions of Natives were forced to endure. The indigenous adoptees of Utah could eventually win their freedom — if they survived to adulthood — unlike the vast majority of African Americans in the South, whose slave status was passed onto their children. Yet all forms of slavery shared key hallmarks that scholars use to identify enslavement. Black and indigenous victims alike were taken against their will, bought and sold and compelled to labor for others without pay.

The existence of Native American slavery was widely acknowledged and openly discussed in the 19th century, as historian Margaret Newell notes. Yet the victims of this brutal commerce — whether in Utah, California, New Mexico or elsewhere — have largely slipped from our historical memory.

As we mark the 401st anniversary of American slavery, the view from Utah and the Far West is essential. America’s slave systems trapped blacks and Indians alike, and reached from one end of the continent to the other.

Sarah Barringer Gordon, Ph.D., is the Arlin M. Adams Professor of Constitutional Law and a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania.

Kevin Waite, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of modern American history at Durham University, Durham, U.K.