The long, hot summer of protest is drawing to a close in an unexpected way: not with the toppling of another Confederate monument, but with the removal of a mural celebrating a former slave.

None of the common combatants in the culture wars – antiracist activists, QAnon conspiracists, or even your casually bigoted uncle – are present this time. The culprit here is one of the nation’s wealthiest universities located in one of its most progressive cities.

UC San Francisco (UCSF) kicked off a firestorm of protest this summer when it announced plans to remove ten New Deal-era murals, including one featuring an African American pioneer, from a central campus building. The removal was necessary, university spokespeople claimed, to make way for a multi-billion dollar campus redevelopment project. As of yet, there are no plans to display the murals again – they’ll simply be stashed in a warehouse – despite loud complaints from virtually every corner of the state.

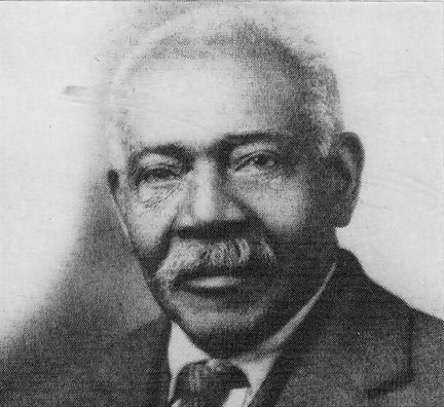

The murals that UCSF seems so eager to forget were once hailed as the “jewel of the university’s art collection.” The Jewish-immigrant artist Bernard Zakheim painted them at UCSF’s request in the late 1930s. They depict scenes from California’s medical history, from the Spanish era into the early twentieth century. Zakheim, a Diego Rivera-collaborator, was regarded as one of the finest muralists of his day.

The murals are significant not only for their aesthetic value but also for their subject matter.

The most celebrated panel features Biddy Mason, a Georgia slave turned California philanthropist and entrepreneur. Born into slavery in 1818, Mason’s road to freedom and eventual fortune was long and tortured. She was forcibly taken from Georgia to Mississippi to Utah and finally to Southern California in the early 1850s. Across this 3,000-mile journey, she remained enslaved.

Only in 1856 – six years after California had technically outlawed human bondage – did Mason finally win her freedom in a Los Angeles courtroom. Despite persistent gender and racial discrimination, she launched a long, successful career in nursing and real estate, eventually accumulating a fortune that made her among the wealthiest women of color in the American West.

The mural – the first known artistic representation of Mason – depicts her tending to patients in the streets of Los Angeles. Shown in the center of a group of white doctors, she radiates authority and healing power. Such positive portrayals of women of color from this period are exceedingly rare. The mural is a tribute to Black empowerment, an urgent symbol for our fractured age. It merits not only preservation but celebration.

The university was apparently ignorant of the mural’s historic and symbolic significance until news broke this July in a Los Angeles Times op-ed. Despite the media scrutiny and public outrage that followed, UCSF has taken few meaningful steps toward safeguarding this important piece of Black history – or any of the other murals for that matter.

So far, the university has played the villain in this narrative. But it’s not too late for administrators to step into the role of hero. To do so requires clear moral leadership and a relatively modest outlay of resources.

UCSF has a $4 billion endowment. Use a tiny sliver of that immense wealth in the service of art and history. Issue a concrete proposal to not only preserve but also to redisplay the murals, whether in a campus building or a designated museum. Numerous art and heritage experts have already stepped forward over the course of this controversy. Draw on their expertise to ensure these murals receive the care and the prominence they deserve.

The historic nature of our present moment lends a special urgency (and irony) to UCSF’s actions.

While Kamala Harris makes history as the first woman of color on a presidential ticket, one of the most powerful institutions in her hometown plans to remove a tribute to another Black female pioneer. As this mural attests, Harris is merely the latest in a long line of barrier-breaking Black women in California.

If there was ever a time to celebrate Biddy Mason and the legacy she left, it’s now.

What UCSF does (or fails to do) will have an impact far beyond the halls of the university or even San Francisco’s arts community. The decision will say a great deal about what images merit preservation, whose stories get told, and ultimately whose history matters.

When even the wealthiest institutions fail to honor our shared cultural heritage, to celebrate Black advancement and the American past, how can we expect others to do the same?

Kevin Waite is an assistant professor of history at Durham University in Britain, and the co-director of a collaborative research project on the life and times of Biddy Mason, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Read the original Op-Ed here.